Tax Counsel

Well-Known Member

A) what happens when the appeal which got reversed by the Supreme Court had itself reversed the trials court decision? In the absence of any more specific directions from the Supreme Court, does reversing the appeal REVIVE the trials court decision? (Remember, we are talking about a CIVIL decision here, not a criminal conviction or acquittal.)

I've gone back to your original questions because it looks to me like this thread has gone a little off track. I'll outline the general process here (in case that did not go to a jury) but to keep it simple, it'll be a case that has just one issue. The exact steps will vary a bit depending on what court system the case is in, but what follows is an overview of the typical process.

1. Trial court releases its opinion on the issue and its order, but the order is not final until the time for appeal has expired.

2. If one of the parties files a timely appeal as a matter of right (which means an appeal that appellant doesn't have to first get approval from the appellate court to file, then the trial court loses jurisdiction over the case and the jurisdiction over the case now lies with the appeals court. That effectively suspends the trial court's order until the appeal is resolved.

3. The appeals court decides that the trial court was wrong and releases its opinion and order in the case, but the decision of that court is not final until the time the parties to file a writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court. That writ asks the Court to accept the case for review.

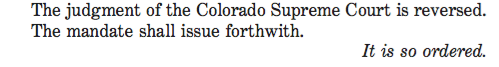

4. If the Supreme Court accepts it for review then jurisdiction is now in the Supreme Court and the action of the appeals court is suspended until the Supreme Court renders its decision. Let's say the Supreme Court decides that the trial court got it right on that one and reverses the appellate decision in full.

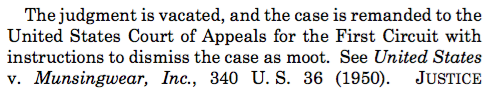

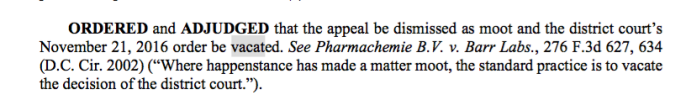

5. The Supreme Court then sends the case back to the court of appeals to take action consistent with the decision of the Supreme Court. Jurisdiction returns to the court of appeals. As the appeals court's earlier order was reversed on the only issue before it, it would issue an order vacating its previous order and send it back to the trial court.

6. Once the case returns to the trial court, the trial court regains jurisdiction. In this simple example the trial court's previous order that was suspended during the appeals process will now become final.

Remember, this is just a general overview of the process of an appeal of a simple case with just one issue to be resolved. Also each step may involve several different actions by the parties and the court.

What I probably need access to is some sort of federal judge's handbook of legal procedure. Are such things available online?

There is no such handbook in the federal system. However, there are rules for the courts to follow. The actions in the trial court are governed by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) and the appellate procedures are found in the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. (FRAP). Each of those pages has download links to PDF versions of their respective rules, since you said you prefer PDFs. You also need to look at any federal statutes that apply to the particular type of action being filed to find the rules Congress set out for that particular claim and look at any local rules that apply to that court (for example, if appealing to the federal Circuit Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, the Tenth circuit has additional rules that must be follows, which may differ from what other circuits have in their local rules.

What exactly are you trying to figure out? What is it about the procedure process in the Trump case that you don't understand or that you think is problematic? Each case is different so the exact steps the case will take along the way from filing the complaint in the trial court to the issuance of the final order will be bit different in each case. So those details are important.